British parents turning to surrogacy tourism in countries blighted by poverty, new figures show

New figures obtained by Finance Uncovered reveal the extent to which UK parents who cannot have children themselves are instead travelling overseas to hire surrogates from countries with significantly higher rates of poverty.

On average, six newborn babies a month were brought into the UK last year by British parents returning from surrogacies in countries such as Nigeria and Georgia, where poverty and maternal mortality rates are much higher.

The figures, obtained from the Government’s Children and Family Court Advisory Support Service (CAFCASS), suggest rising demand for so-called “low cost surrogacy tourism” and come as major reforms to Britain’s surrogacy laws are expected to be unveiled by the Law Commission on Wednesday.

It is expected that the Law Commission, a Government funded body, will publish a draft bill that goes some way towards liberalising UK laws, accepting that paid-for surrogacy is a reality and introducing some US-style regulations to help guard against exploitation.

But while commercial surrogacy in some US states is legal and heavily regulated, it is also expensive, costing parents upwards of $120,000. Scores of British parents visit America each year and spend this amount on a surrogacy, but for others it is prohibitively expensive.

Growing demand from would-be parents who are unable to afford US-style surrogacy bills has led to a rise in the number of agencies specialising in so-called “low-cost surrogacy tourism”, using surrogates, egg donors, IVF clinics and maternity units in in higher poverty countries.

Even if UK law is liberalised along US-lines, the Law Commission already anticipates that low-cost surrogacy tourism is likely to remain an option that will continue to appeal to some British parents.

Specialist low-cost agencies make considerable profits by matching women in countries where poverty rates are higher — often unmarried, near-destitute and raising young children of their own — with infertile and gay commissioning parents from wealthier countries such as the UK.

Addressing the concern…

The Law Commission study, which has been years in the making, in large part stems from a concern about parents taking this route.

The thriving low-cost surrogacy industry has in part been fuelled by the falling cost of in vitro fertilisation (IVF) technologies – that is, the ability to fertilise an egg outside of a woman’s body, in a laboratory – pioneered in Britain in 1978.

Cheap air travel and the ability to both recruit women and market surrogacy tourism via the internet have also helped many international surrogacy agencies to flourish in the last decade.

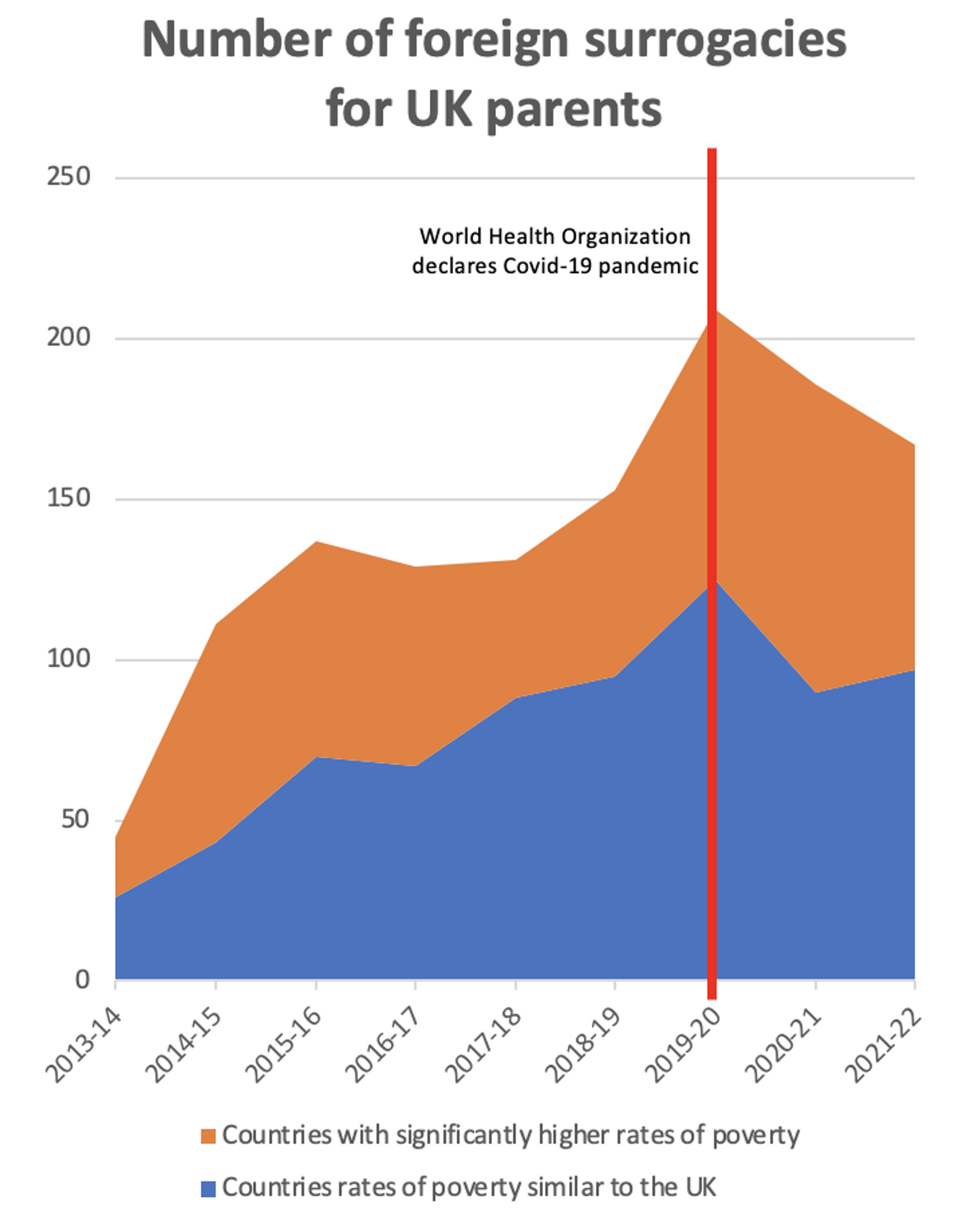

Source: Finance Uncovered analysis of CAFCASS data, extracted from parental order applications

The CAFCASS figures, which Finance Uncovered have published here, suggest this has become a well-trodden route for British would-be parents who cannot find a surrogate in the UK and cannot afford a US surrogacy.

The number of British parents traveling to countries for surrogacy where poverty is higher rose from 19 in 2014 to 96 in 2021, before dipping slightly in 2022 because of the disruptions caused by the coronavirus pandemic.

In that nine-year period, British parents have sought UK parental orders for at least 570 babies born to surrogates from such countries, CAFCASS figures show. These include 201 born to surrogates in Ukraine, 182 to surrogates in India, 80 to surrogates in Georgia, 33 to surrogates in Nigeria, and 26 to surrogates in Thailand.

An early boom in surrogacy tourism in India and Thailand was effectively halted in the mid-2010s by a series of government clampdowns. Thereafter Ukraine and Georgia emerged as the leading low-cost destinations, though neither permit gay would-be parents.

Since the Russian invasion in February last year, many surrogacy agencies and clinics in Ukraine have been forced to close though some continue to operate.

The Baby Broker Investigation

An investigation by Finance Uncovered and media partners last year raised serious questions about New Life, one of the world's largest low-cost surrogacy agencies.

New Life, which prior to the coronavirus pandemic claimed to be transferring between 80 and 100 embryos a month to surrogates, has operated in India, Thailand, Cambodia, Georgia, Ukraine, Kenya, Nepal and Mexico, though some branches are now closed.

A journalistic investigation into New Life’s activity across four continents, known as the Baby Broker Project, found the agency:

- Recruited vulnerable women, such as domestic violence victims, as surrogates

- Negotiated deals in which surrogates were paid a delivery fee of $12,500 while the agency got $4,500

- Boosted commissioning parents’ chances of a baby by routinely arranging the transfer of two or three embryos to surrogates, a gamble that also hugely increases the risk of surrogate death in childbirth

- Advised commissioning parents that Down syndrome babies can be abandoned in Ukrainian orphanages

Mariam Kukunashvili, New Life's founder, labelled the work of investigative journalists as 'psychological fascism'

New Life told reporters many of these findings were historical. It no longer transfers more than one embryo to a surrogate, and controversial advice to parents concerning newborns with Down Syndrome has not appeared on its websites since 2015.

New Life said it was proud of its recruitment record, which “assisted many people to overcome poverty and earn a living”.

Britain’s existing surrogacy laws, which date back to 1985, are designed to limit the risk of exploitation. In particular, they are meant to prevent agencies and would-be parents from using the promise of money to pressure poor and vulnerable women into signing contracts in which they feel trapped.

Current laws make such contracts unenforceable in the courts. They also make it a criminal offence for commercial agencies to operate in the UK — though Finance Uncovered found New Life operated openly and without challenge, including through the use of a UK-registered shell company.

Surrogacy: A 'culture wars' flashpoint

At the heart of the surrogacy debate are opposing views on whether would-be parents ought to be able to pay women for their services as a surrogate. Existing law permits voluntary payment of “expenses reasonably incurred”, but in practice much larger amounts regularly change hands, unchallenged by the courts.

Despite its acknowledged flaws, not everyone is in favour of liberalising existing laws. Some Christian conservatives and radical feminist groups oppose all forms of surrogacy. A debate about the ethics of “wombs for hire” and “pimping pregnancy” has become a culture war flashpoint.

In the meantime, outdated laws in Britain are pushing demand for surrogacy offshore, sometimes to parts of the world where the risk of exploitation is higher.

More than half of British parents who have a child through surrogacy do so overseas, CAFCASS figures suggest. Despite the impact of the covid pandemic and the war in Ukraine (a leading low-cost surrogacy destination), the UK family court received 320 applications for surrogacy-related parental orders last year, with 55 percent relating to overseas surrogacies.

Parental orders are required in the UK to transfer legal parenthood from a surrogate to the commissioning parents. Without such an order, the law regards the surrogate as the child’s legal parent — something the Law Commission is expected to change.

No UK government agency collects comprehensive data on where British parents chose to travel for offshore surrogacies. So Finance Uncovered asked CAFCASS to extract and anonymise data from parental order applications in its archive in order to show the countries where surrogates were resident.

The Law Commission, academics and others consider data from these applications to be the best available proxy for surrogacy destinations, though an unknown number of parents may not bother to obtain an order from the court.

The Commission has already signalled it thinks existing surrogacy law is not being followed and is effectively broken. Campaigners on both sides of the debate on the ethics of surrogacy will be closely watching how far the Commission goes in supporting payments for a surrogate’s services that are contractually enforceable.

The Commission has already made clear it intends to reject calls from Evangelical and radical feminist groups for surrogacy to be banned or for existing laws to become more restrictive.

Meanwhile, it has indicated that it expects to keep in place the ban on for-profit surrogacy agencies, such as New Life, operating in the UK.

While it hopes legal reforms will encourage a greater proportion of would-be parents to choose surrogacies in the UK, the Commission has already said there are limits to what UK reforms can achieve internationally.

"Ultimately, only an international convention, as exists in respect of inter-country adoption, can ensure a uniformity of approach to guard against exploitation," said professor Nicholas Hopkins, the Law Commissioner leading the UK law reform proposals.

Meanwhile, the organisers of the Fertility Show, Britain’s biggest annual trade fair for would-be parents, have told Finance Uncovered that New Life will not be among exhibitors at its next event in May, despite being a regular fixture at past shows in London’s Earls Court.

“The Fertility Show works hard to ensure that all its exhibitors are ethical,” Laura Biggs, chief executive of Intuitive Events, said in an emailed statement. “We can confirm that the company New Life Georgia are not exhibiting with us.”

The Baby Broker project involved journalists from Animal Politico in Mexico, iFact in Georgia, The Observer from the UK and Eesti Päevaleht from Estonia. Freelance reporters from Kenya and Cambodia also took part. The project was coordinated by Finance Uncovered and supported by funding from the Pulitzer Center.

In reply to the work of investigative journalists, the founder of New Life, Mariam Kukunashvili, published a post to her 47,000 Facebook followers, accusing reporters of manufacturing “lies and ugly headlines.” She said the reporting was “nothing less than psychological fascism.”

* Main image by Anadolu Agency/Getty. A baby born through surrogacy in Ukraine in 2022, one of the most popular destinations for UK parents seeking surrogate mothers before the outbreak of war with Russia.