Dam winners: Mining bosses at companies being sued over Brazil’s worst environmental disaster awarded $516m in pay since 2015 catastrophe

The 38 top executives at BHP and Vale, the two mining companies that own the Brazilian firm behind the 2015 Fundão dam disaster, have been granted pay and bonuses awards valued at $516 million since the avoidable catastrophe occurred almost nine years ago, according to a Finance Uncovered analysis.

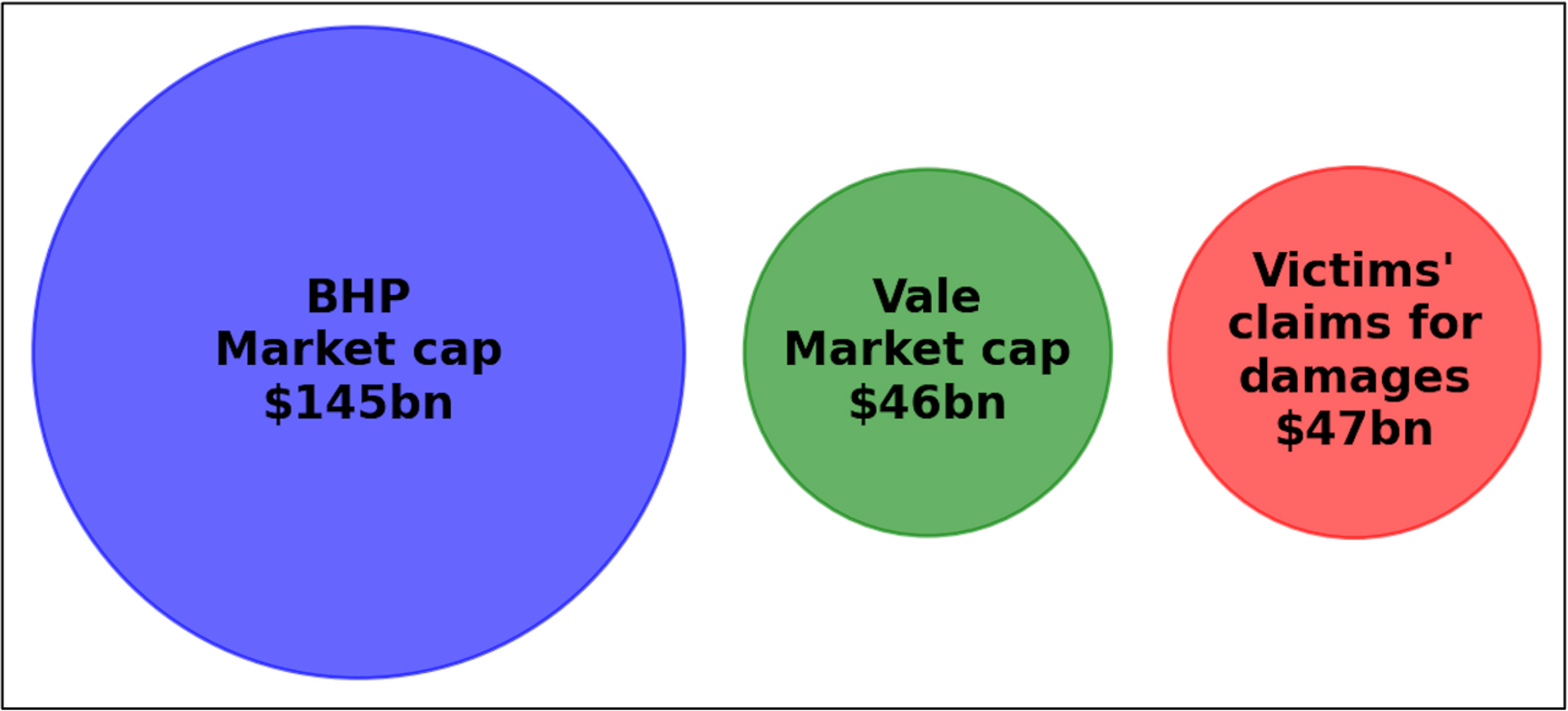

The size of the bosses' rewards are revealed on the eve of a major battle in the UK courts in which more than 600,000 victims are suing the companies for £36 billion ($47 billion) in compensation. The case starts on Monday and is expected to last several months.

In contrast to the salaries, benefits, and bonuses racked up by executives at BHP and Vale, the past nine years have been considerably less generous to victims of the 2015 disaster. Nineteen lives were lost when the dam collapsed and entire communities whose lives were thrown into turmoil by the environmental disaster are seeking urgent redress.

So far, the mining companies involved say they have spent $7.9 billion. But in a surprise last minute move earlier this weekend, BHP announced its subsidiary BHP Billiton Brasil, together with Vale and Samarco Mineração SA, was close to agreeing a fresh settlement with state and federal officials.

In a statement, BHP suggested the amount spent on compensation and remediation could eventually rise to $32 billion, albeit over 20 years.

Pogust Goodhead, the law firm representing disaster victims in the UK courts, described the statement as “a desperate attempt by BHP to avoid being held accountable in court for the acts that led to the collapse of the Fundão dam on November 5, 2015.”

The law firm noted most of the funds proposed in BHP’s statement were earmarked for federal and state governments, and were not direct compensation for individual victims and communities.

Through the UK courts, disaster victims are seeking damages of £36 billion ($47 billion), which is equivalent to almost a quarter of the combined share value of both companies.

Share values (market capitalisation) of BHP and Vale alongside the estimated value of damages sought in the UK class action by 620,000 victims of the 2015 dam collapse

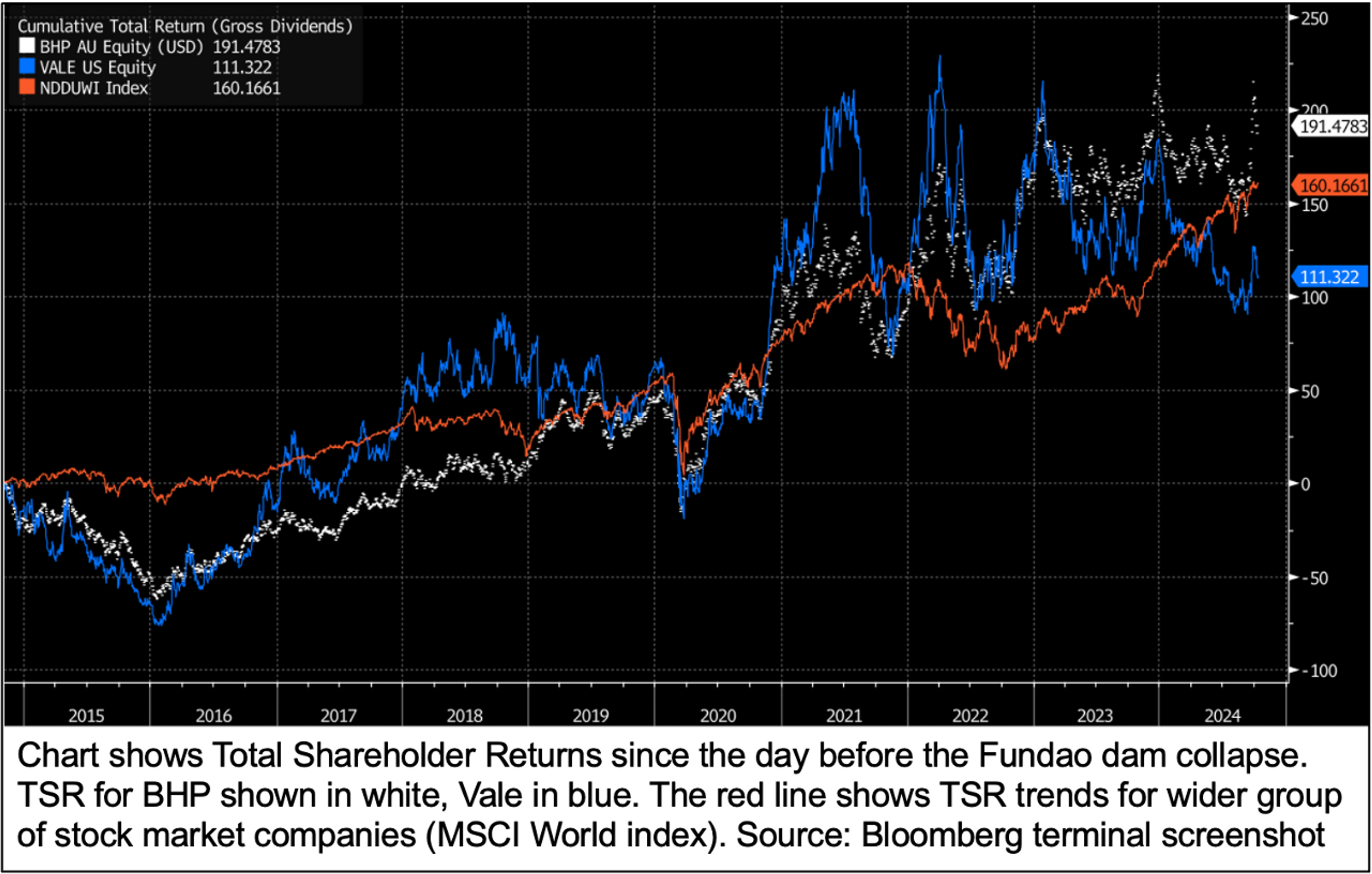

While frustrations and delays over victim compensation have been distressing for many in the Doce Valley, they have had a favourable impact on shareholder returns — and consequently on executive pay.

In total, Finance Uncovered’s analysis found 21 Vale executives were granted salary, benefits and bonuses valued at $293 million for the nine years to December 2023. Meanwhile, 17 BHP executives were granted $223 million for nine years to June 2024. These figures were taken from annual reports but the two groups may use slightly different methods to value multi-year, share-based awards, so may not be directly comparable.

The biggest component of the pay awards were bonuses tied to executives’ efforts to drive up their respective groups’ share price and dividend payouts.

In addition to its executive pay analysis, Finance Uncovered, together with Brazilian online newspaper Metrópoles, can also reveal that, before disaster struck in 2015, Samarco Mineração SA, the BHP-Vale joint venture that ran the dam and associated iron ore mining operations, had heavily under-estimated the likely cost of a dam rupture.

Internal Samarco documents from 2014 show the company had projected a “Máxima Perda Previsível” (Maximum Foreseeable Loss) of just $2.6 billion under its disaster-risk modelling.

Samarco even down-graded the likelihood of a dam failure in 2014 — a move which may have led to a small increase in executive bonuses. Samarco declined to confirm this.

The following year, just three months before disaster struck, internal Samarco documents show the company’s executives were judged to be on track to get the maximum allocation of their bonus linked to “risk management” — including the risk of dam failure.

Andrew Mackenzie, BHP AGM 2016 (Photo: Patrick Hamilton/Bloomberg via Getty Images)

In the days after the disaster, BHP’s then chief executive Andrew Mackenzie (pictured above), rushed to Mariana, the nearest town to the dam, to meet with members of the local community. Seeming to read from prepared notes, he said: “The people of Brazil, the people of Mariana, have my absolute determination that we will fully play our part in helping to rebuild your homes, your community and your spirit.”

Two weeks later, he used the same formulation of words — “my absolute determination” — in a speech to BHP’s annual shareholder meeting in Perth, Australia. “We are deeply sorry to everyone who has and will suffer from this terrible tragedy,” Mackenzie said. “They have my absolute determination that we will fully play our part in helping Samarco [BHP’s joint venture with Vale] reconstruct homes, community and spirit.”

If that sounded like a personal guarantee from the BHP boss that swift compensation was to follow, it was not. Mackenzie left BHP in 2020.

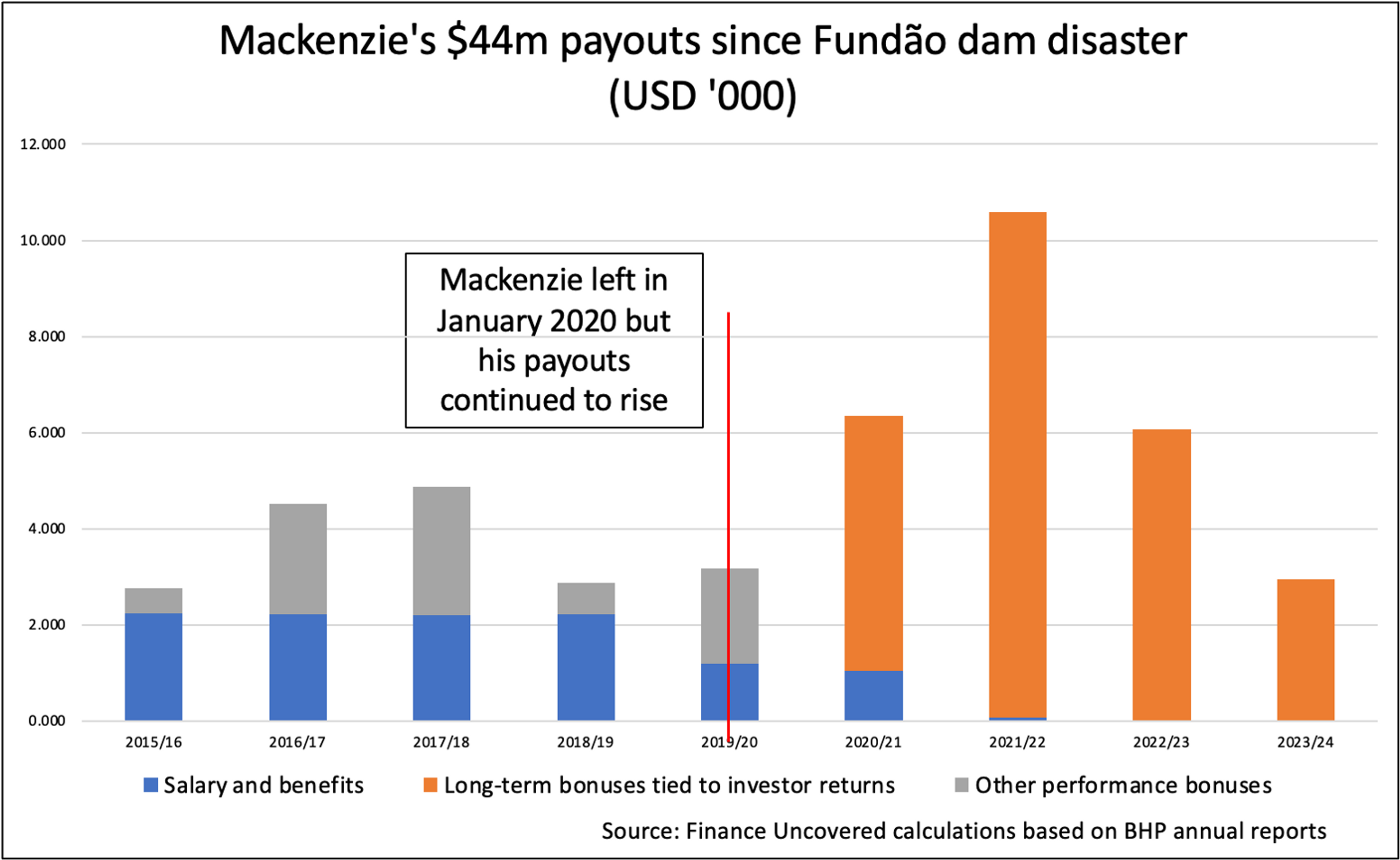

Nevertheless, for the five years between the Fundão dam disaster and his departure, he collected pay and bonuses worth $44.2 million, according to Finance Uncovered analysis.

This is despite a much-reported decision not to pay Mackenzie an annual short-term bonus of almost $1.6m for the year in which the dam collapse occurred.

Despite the high-profile hit to his pay in 2016, many of his most lucrative bonuses only matured in later years. This includes $5.3 million in BHP shares that were released to Mackenzie in 2020, eight months after his departure. These awards had been conditionally allocated to him just one month after the Fundão dam collapse in 2015.

A further $20.1 million in restricted shares were released to Mackenzie in 2021, 2022 and 2023. Although BHP did not explicitly disclose all these releases, Finance Uncovered has been able to calculate the value of Mackenzie’s restricted shares by reference to comparable payouts to other BHP executives. Not included in Finance Uncovered’s calculation is a likely final release of shares, worth up to $1.1 million, which was scheduled for this summer, subject to shareholder return targets being met.

Each of these annual releases was designed to reward Mackenzie for his part in delivering investment returns for shareholders over a five-year period, with BHP’s performance benchmarked against returns generated by a group of similar multinational corporations. Similar incentives were in place for other BHP executives and for counterparts at Vale.

Mackenzie now serves as chair of the British oil and gas group Shell, and shortly after leaving BHP he was awarded a knighthood in the UK for his services to business and to UK-Australia relations.

Finance Uncovered tried to contact Mackenzie for comment but were unable to reach him.

Because Brazilian pay disclosures are not broken down by individual executives, it is impossible to learn how much was awarded to former Vale chief executive Murilo Ferreira, who stepped down in 2017, or to any other executive at the Brazilian mining group.

Obstruction and delay

On 5 November, 2015, the Fundão dam, housing the equivalent of 16,000 Olympic swimming pools of mining slurry, burst its banks sending a wall of mining waste and mud crashing down the Doce river valley, killing 19 people, washing away villages, and bleeding out, almost 400 miles away, into the Atlantic Ocean.

Given the scale of destruction, the tally of 19 lost lives was mercifully low. But hundreds of thousands of people lost their homes and livelihoods, or were otherwise impacted. This included the indigenous Krenak people, for whom the river was sacred.

Lawyers for BHP have spent the past five years arguing that victims should have no standing in the UK courts, insisting the case — if it had merit at all (and they say it does not) — ought to be heard in Brazil. Vale takes a similar view, though it is no longer a defendant in the UK proceedings, having instead agreed to foot half of any damages order imposed on BHP if it loses.

Why is the claim being brought in the UK at all? Through an accident of corporate history, in 2015 BHP’s global corporate structure included a key artery of ownership, connecting its operations in Brazil up to what was then a dual-listed pair of companies that together functioned as BHP, with shares trading on stock exchanges in both London and Australia. The London listing has since been dropped. Nevertheless, this past connection has been sufficient to give the claimants a foothold in the UK courts.

Attempts by BHP and Vale to get the UK class action thrown out of court have failed. Indeed, lawyers for the victims successfully argued that the compensation process in Brazil has not been able to cope with the volume of claims, in part because of the obstructive behaviour of those bodies set up by BHP, Vale and Samarco to resolve victims’ claims.

In particular, lawyers for those impacted by the disaster point the finger at Renova Foundation, set up by the mining companies for this purpose. They accuse Renova of being obstructive and foot-dragging; imposing complex red tape and unfair qualification criteria on claimants; and using deliberate procedural tactics to frustrate claimants in the courts.

And behind Renova, the victims’ lawyers argue, this Renova process has always, in effect, been controlled by BHP and Vale. This allegation is contested by the mining companies, who insist the foundation is independent.

When, two years ago, the UK Appeal Court ruled that claims against BHP and Vale would be allowed to go to trial, Lord Justice Underhill made clear that those acting for the victims had — at least provisionally — made a strong case.

“Taken at face value they paint a coherent picture of widespread inadequacies in the redress available from Renova, within a reasonable time or at all,” he said.

When the lawyers gather on Monday morning to begin months of argument and testimony, both sides will have a chance to lock horns once again.

In written submissions, lawyers for BHP have already set out why they will ask the court to reject “these ill-conceived proceedings”. Lawyers for BHP have told the court “There is … ample opportunity for victims to receive full redress under sophisticated and well-established procedures in Brazil.”

The mining industry has always been high risk, both for workers and for those who live near extractive sites. The history of the mineral rich Minas Gerais state in South-Eastern Brazil, where Fundao dam was located, is littered with deadly episodes.

At the same time, the industry dominates. Minas Gerais — literally meaning “General Minerals” — is one of two states that produce almost all of Brazil’s valuable iron ore, helping make the country the world’s second largest exporter last year.

The International Labor Organization (ILO), has estimated that although mining accounts for only one percent of the global workforce, it is responsible for about eight percent of fatal accidents at work.

The picture is much better at mines operated by some of the world’s largest mining groups, many of which — like BHP and Vale — are stock market listed companies. The International Council on Mining and Metals (ICMM), an industry body which tracks safety data, is made up of 25 such firms.

For 2015 — the year of the Fundão dam disaster — ICMM figures record there were four on-site fatalities at BHP mines. There is no equivalent figure available for Vale, which did not become an ICMM member until two years later.

The 19 fatalities caused by the disaster in Brazil, including the deaths of 14 dam workers, were not recorded in the ICMM statistics. This is because the tailings dam was not operated by either BHP or Vale, but rather by the two firms’ joint venture, Samarco.

Whether BHP and Vale can nevertheless be held accountable is one of the central issues to be determined in the UK class action court case.

Though Samarco’s board was entirely composed of top BHP and Vale executives, below these directors day to day operational control was delegated to a committee of Samarco executives charged with running the business day to day.

In the aftermath of the disaster, much was written about whether Samarco executives should have paid greater heed to warnings that the dam was showing signs of instability. And the UK class action claim, will try and establish what, if anything, was also known about these concerns by BHP and Vale.

Samarco executive incentives

Whatever information about dam risks was or was not known to Samarco bosses, Finance Uncovered and Metrópoles have sought to look into another factor influencing decision making: bonuses.

One was the incentive structure that had been embedded into the Brazilian company’s pay packages by the Samarco remuneration committee, made up of two senior bosses from BHP and Vale.

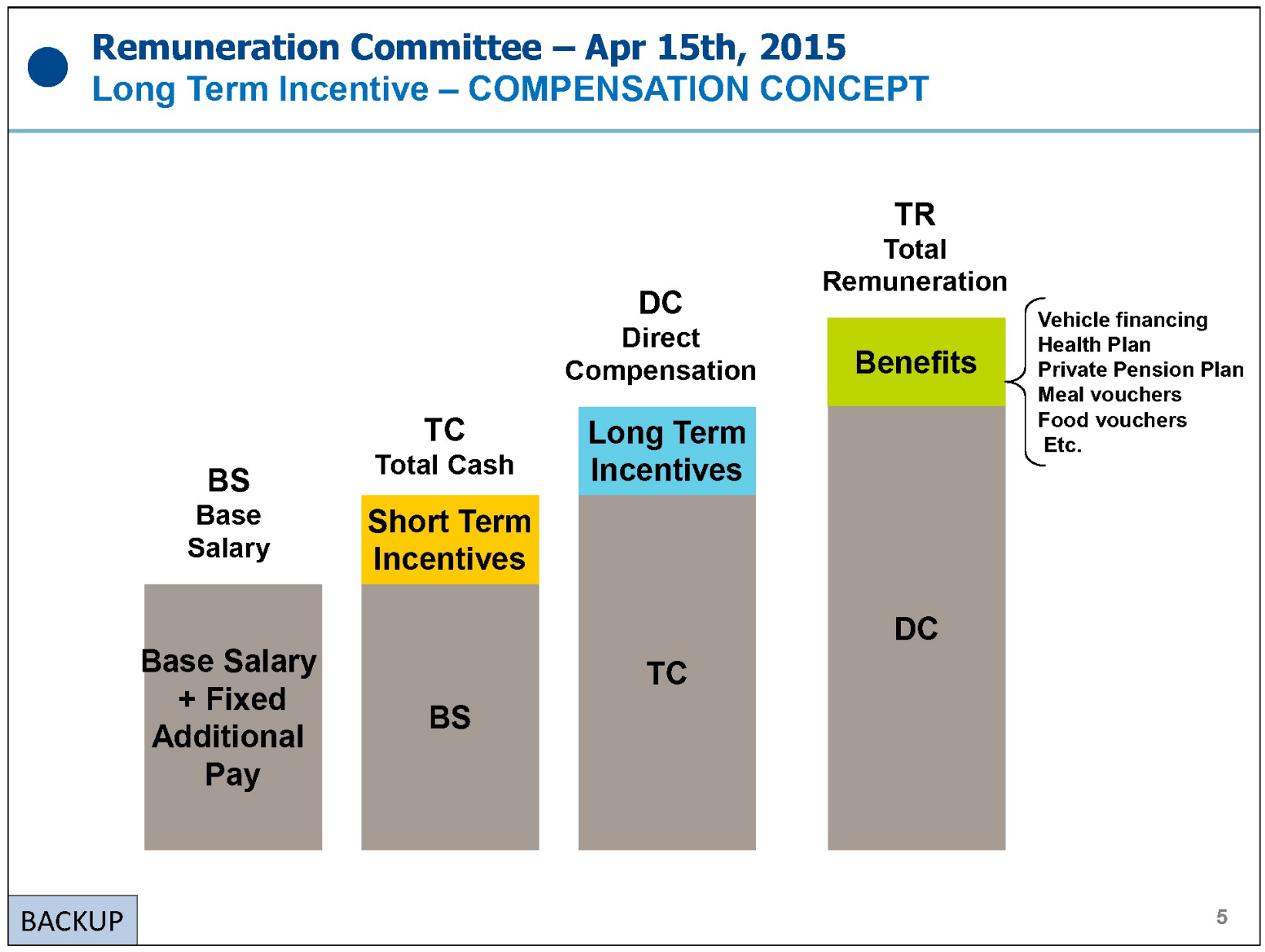

Documents obtained from Brazilian court proceedings (unconnected to the UK claim), include internal Samarco files setting out details of executive bonus schemes that have not been reported before. They paint a picture of a bonus culture highly focused on financial returns and delivery of capital projects, but with only one small element linked to the risks faced by the business, its employees, local communities and the environment.

The documents show that BHP and Vale made up the remuneration committee responsible for setting Samarco executive pay packages. Each package comprised of four pillars, as set out in the chart below. Bonuses were included in the two “incentive” pillars and were linked to various performance criteria, most of which involved financial targets.

Samarco executive pay "slide" presented at April 2015 remuneration committee meeting of Samarco board, consisting of BHP and Vale bosses. Made public during court proceedings in Brazil.

Only within the short term incentive pillar was there a small bonus component linked to a list of 20 risks faced by the Samarco — including just one risk that specifically envisaged a tailings dam failure.

As late as August 2015, an internal Samarco document that tracked progress towards these bonus targets showed that the remuneration committee (i.e. BHP and Vale bosses) was expecting to give Samarco executives the maximum score for their management of risks.

This full-marks assessment of Samarco’s risk management was made less than three months before the Fundão dam collapse. It appears to have given little or no weight to the warnings that Samarco had received about cracks in the dam, or to the increase in risk caused by decisions to raise the height of the dam.

Risk down-played

Elsewhere, other internal Samarco documents show how, in the previous year, Samarco had in fact down-graded the perceived risk of a dam collapse (see Slide from Samarco presentation below). We asked Samarco whether this down-grade caused a small positive adjustment in 2014 executive pay, but the company did not respond.

According to one presentation to the Samarco risk subcommittee, the risk value given to dam failure was lowered because Samarco executives had provided a list of fresh mitigation and contingency measures and because new studies confirmed the risk of an earthquake or mine-blasting causing damage severe enough to threaten the dam was very low.

The document also summarised what the Samarco board envisaged a worst-case dam failure would look like, forecasting a maximum foreseeable loss of $2.6 billion, with two fatalities at the Fundão dam, two in the nearby village of Bento Rodrigues, and the death of perhaps one passerby. Under this imagined scenario, a surrounding area of about 30 hectares would be polluted or damaged and would take about five years to recover.

The reality, of course, was far worse.

Finance Uncovered and Metrópoles asked Samarco, BHP and Vale whether, with the benefit of hindsight, they felt due weight had been given to the risk of the dam collapse. None of the companies answered this question or others, instead providing short statements. BHP and Samarco added that legal proceedings and settlement negotiations restricted what they could say.

Vale said the Renova Foundation had already compensated about 430,000 people. “In total, more than R$37 billion has already been invested by Vale, BHP and Samarco in actions to compensate and repair the environment and infrastructure affected,” it said. Vale said the UK lawsuit “deals with issues already covered in Brazil, whether by legal proceedings or by the repair work carried out by Renova”

Samarco said: “The company reaffirms its commitment and remains committed to the full remediation of the damages caused by the collapse of the Fundão dam.”

BHP said: “”BHP continues to defend the legal action in the UK, which duplicates the efforts already ongoing in Brazil and if successful would see up to 30 per cent of any compensation awarded to an individual claimant diverted to the class action lawyers and funders associated with the case.”

In response, a spokesperson for Pogust Goodhead confirmed it was charging individual claimants in Brazil 30 percent of the value of their claim. Businesses were charged between 20 and 30 percent, and there was no charge for indigenous and traditional communities. The spokesperson noted that no such legal costs would have been necessary had victims’ claims been settled appropriately.

Little more than three years after the Fundão dam collapse, a second tailings storage facility, called Brumadinho dam, also experienced a catastrophic rupture. Although the Brumadinho dam contained less mud and industrial waste, its collapse in early 2019 was more lethal, killing at least 270 people. The Brumadinho dam was operated by Vale and, like the Fundão facility, it was located in the central region of Minas Gerais state.

Fatalities resulting from the Fundão dam collapse were lower than they might have been because the rupture took place during the day, shortly after the school day finished. Had it happened at night, the death toll could have been much worse.

*Additional reporting: Malia Politzer

*Fact checking and editing: Ted Jeory and Nick Mathiason

* Main image: Fundao dam disaster - one year on (Getty)