Luanda Leaks: Isabel dos Santos and her Cape Verde banking paradise

A major leak of secret documents detailing the finances of Africa’s richest woman has raised serious questions about the role played by the winter sun islands of Cape Verde as she built her controversial business empire across the world.

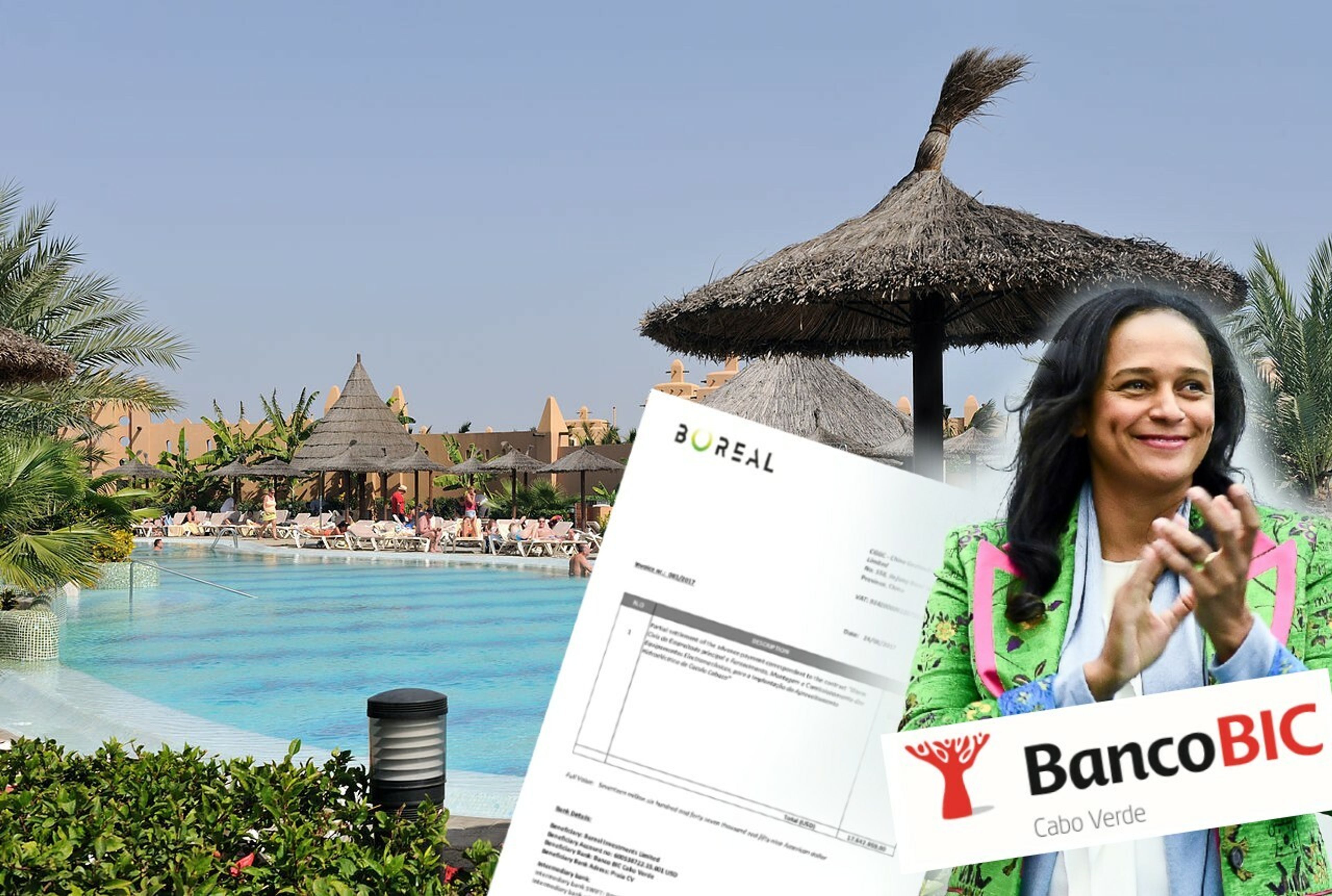

The cache of files, known as the Luanda Leaks, show how Isabel dos Santos, the billionaire daughter of Angola’s former president, used her own bank on the trendy tourist archipelago to route millions of dollars in payments from Chinese and European contractors working on construction projects in her father’s country.

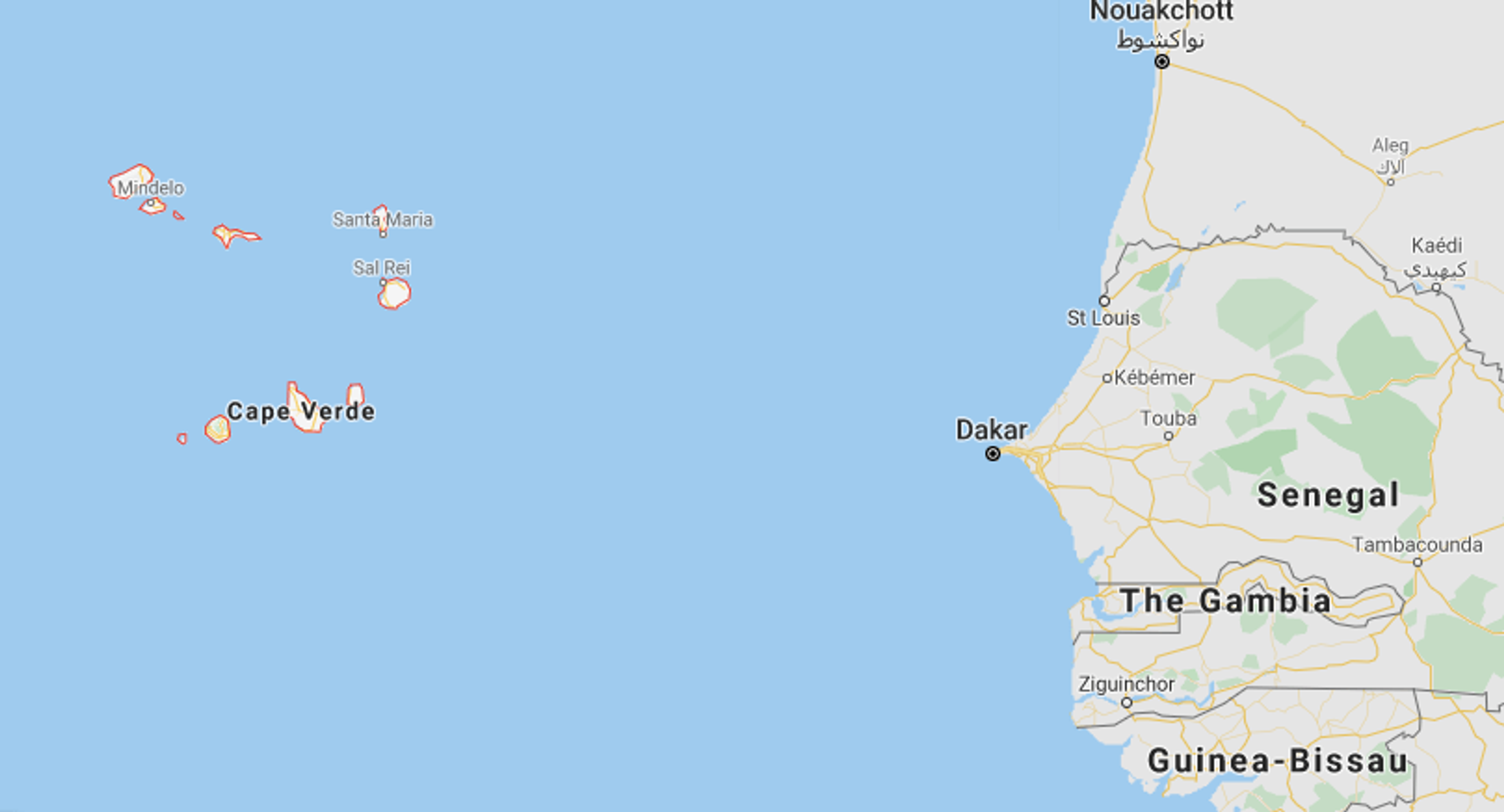

The payments through the lighter touch regulatory environment of Cape Verde – a Portuguese-speaking archipelago off the west coast of Africa – were ordered at around the time scrutiny of her business dealings mounted in the wider international banking system.

Ms dos Santos, then a “politically exposed person” (PEP) in anti-money laundering terminology, had bought into the bank in 2013. This was the same year Cape Verde’s regulators seemingly waived their ownership rules and granted it a banking licence.

Experts say the findings suggest reforms in global standards are needed over whether PEPs can own banks.

Cape Verde – a weak actor in banking regulatory system

Tom Keatinge, director of the Centre for Financial Crime and Security Studies at the Royal United Services Institute think tank, said: “A PEP owning a bank in a weakly regulated jurisdiction like Cape Verde represents the perfect combination for a potential risk of facilitating money laundering.”

He added: “A weak actor like Cape Verde offering international banking services represents a systemic vulnerability for the global financial system.”

The princess and her country’s paupers

Ms dos Santos, 46, who has rubbed shoulders with celebrities Kim Kardashian and Paris Hilton, has been celebrated as a highly successful businesswoman – even previously feted at the Davos World Economic Forum – but is now reeling from a string of allegations that suggest her wealth was a direct result of her father’s autocratic rule in resource-rich Angola.

Jose Eduardo dos Santos (pictured below with Isabel), who served as president from 1979 to 2017, is suspected of corruption on a massive scale, while the majority of the country’s population live on $2 a day.

Since he stepped down, the focus on his daughter’s businesses has intensified.

In August, Finance Uncovered revealed the details of her London mansion, and last month her assets in Angola – including a telecoms company and a bank – were frozen over allegations she owed the state some $1bn.

This week, she has faced further corruption allegations through the Luanda Leaks project, a collaboration coordinated by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) based on documents provided by the Platform to Protect Whistleblowers in Africa PPLAAF, a Paris-based advocacy group.

The allegations have centred on her business empire, which includes consulting and telecoms companies and even a diamond retailer, and the western advisors who helped her.

The Prosecutor general in Angola vowed on Monday to use “all possible means” to return Isabel dos Santos to Angola.

Dos Santos denies all

Ms dos Santos did not respond to our enquiries but in an interview with BBC Africa said all allegations against her were “completely unfounded” and “orchestrated by the current government that is completely politically motivated”.

She added: “I can say my holdings are commercial, there are no proceeds from contracts or public contracts or money that has been deviated from other funds.”

Her father did not respond to questions posed by the ICIJ.

Cape Verde: Not just tourists who are welcome

As part of the ICIJ project, Finance Uncovered worked with journalists in Cape Verde to reveal the billionaire’s moves into the up-and-coming tourist hotspot – a country marketing itself as paradise islands 400 miles off the coast of West Africa.

Popular with UK holidaymakers and celebrities, the finale of Channel 4’s Celebs Go Dating was filmed there in 2018.

The volcanic islands have a close connection to Angola through their former colonial rulers Portugal. Portuguese is the official language in both countries.

With a population of just 500,000 people, the country has attracted massive investment into its tourism industry over the past 20 years. More recently plans for a controversial mega-casino funded by Chinese investors from the former Portuguese colony of Macau have also been unveiled.

But in 2013, Cape Verde’s National Assembly introduced tax incentives to make the islands attractive to offshore banks.

The same year, Ms dos Santos bought into Banco Bic Cabo Verde. This would be a “sister” to her Angolan and Portugese banks, which were owned by the same investor consortium.

Two years later, as she became the majority shareholder, the bank ramped up its dealings with these “sisters”, a move that increased its profits to a high of €12.9m by 2017.

The Cape Verde bank also became a significant part of her own payments system as concern grew about her politically exposed status elsewhere in the international financial environment.

Finance Uncovered has found that between 2016 and 2017 her companies used accounts at the bank to invoice for more than $35m they were owed for contracts in Angola.

How owning your own bank can be useful…

One of these companies was Boreal Investments Limited, a Hong Kong company which in June 2015 was awarded 37.5% of a state contract to construct the Caculo Cabaca dam on the river Kwanza, Angola.

The $4.5bn mega-project, intended to increase Angola’s total grid capacity by 43%, was financed by a loan from Chinese state owned bank ICBC.

The Luanda Leak files suggest that in 2015 Boreal’s account at Hang Seng, a subsidiary of HSBC, was shut down after dos Santos’ advisers informed it she was the owner of the company.

PEPs are considered high risk because of their potential exposure to bribery and corruption by virtue of their position. As a consequence, banks are required to perform enhanced due diligence before taking on such clients.

It is not clear whether Boreal was able to find another bank in Hong Kong. But in Boreal’s invoice for the advance payment under the dam contract in 2017, it asked its Chinese partner CGGC, a state-owned engineering company, to pay $17.5m to its account at Banco Bic Cabo Verde.

According to Maira Martini, a money laundering policy expert at Transparency International, this payment order should have raised red flags because it involved a bank account in a third country. She said the banks involved should have raised official “suspicious activity reports” to warn of a possible money laundering risk.

Banco Bic Cabo Verde has not responded to any requests for comment.

In June 2018, the new Angolan government, which alleges the contract price was inflated by $1bn, removed Boreal from the contract.

Ms dos Santos strenuously denies the allegation, citing a new presidential decree which has increased the price by a further $1.2bn. Her lawyers said that in Angola, “public tenders are not required or applicable to all public contracts”.

Boreal launched arbitration proceedings against CGGC in August 2018.

…but a PEP owning a bank can be a problem

Policy experts believe bank ownership, and some control of the payments system, is increasingly a key issue in the fight against corruption and money laundering.

Tom Keatinge, of RUSI, says “the potential for corrupt use of a bank by an owner is considerably more than if the bank was owned by a third party”.

He said: “A bank is unlikely to apply financial crime compliance controls to transactions that are conducted on behalf of the owner.”

This is one of the reasons that most countries have strict regulations on who can own banks or hold positions of power within them. But the files show how Cape Verde’s own rules were bypassed when Banco Bic Cabo Verde was granted its license to operate.

Leaked documents show that Ms dos Santos’s co-investors applied significant pressure and demands on the central bank regulators even before they went ahead with their €28m purchase in 2013: in their application for a banking licence, they said a precondition of their investment was for the islands’ Finance Ministry to waive its requirement that offshore banks operating in the country were at least 15% owned by a bank in an OECD country.

Banco Bic Cabo Verde’s proposed owners were individuals and investment vehicles in turn owned by Isabel dos Santos and other individual investors.

The Finance Minister at the time was Cristina Duarte, a former Vice President of Citibank in Angola. When Finance Uncovered called her to ask questions about the issue, including whether she personally knew Ms dos Santos, she appeared to hang up.

Reaction in Cape Verde

The central bank in Cape Verde has failed to answer questions we asked. And Cape Verde’s Finance Minister, Olavo Correia, has cancelled two scheduled interviews.

However, a former senior member of the Cape Verde Cabinet did speak on condition of anonymity.

The former minister said government members have been “extremely dubious” about decisions taken over the operation of the country’s offshore banking sector.

The former minister said that when it came to foreign investment in the country, past governments had lost their capacity to critically assess how, and whether, the investments would benefit citizens.

Despite four years of generous tax breaks to the offshore banking sector, these offshore banks employed just 86 people at the end of 2017, of whom only 51 were Cape Verde nationals according to figures provided by the International Monetary Fund.

Bic Cabo Verde was given €8.5m in corporation tax breaks from the government between 2013 and 2018, but the bank’s non-director wage bill was about €130,000 annually.

What banking regulators need to change

The Cape Verde government is not the only institution that let Ms dos Santos own a bank. The Portuguese authorities also did.

In its response to the ICIJ, a spokesperson for the Bank of Portugal said the European Central Bank had assessed Ms Dos Santos as a bank owner in 2016. European banking regulations require that bank owners are assessed on the basis of their “reputation”.

According to Transparency International’s Maira Martini, this points to a gap in global financial regulations. She said authorities should take into someone’s status as a PEP when making decisions on awarding banking licences.

* Additional reporting: Margarida Fontes

* Editing by Ted Jeory and Nick Mathiason